Email was never built for privacy. It’s closer to a digital postcard than a sealed letter, bouncing through and sitting on servers you don’t control, and mainstream providers like Gmail read and analyze everything that is inside.

Email isn’t going anywhere in our society, it’s baked into how the digital world communicates. But luckily there are ways to make your emails more private. One tool that you can use is PGP, which stands for “Pretty Good Privacy”.

PGP is one of the oldest and most powerful tools for email privacy. It takes your message and locks it with the recipient’s public key, so only they can unlock it with their private key. That means even if someone intercepts the email, whether it’s a hacker, your ISP, or a government agency, they see only scrambled text.

Unfortunately it is notoriously complicated. Normally, you’d have to install command-line tools, generate keys manually, and run cryptic commands just to send an encrypted email.

But Proton Mail makes all of that easy, and builds PGP right into your inbox.

How Proton makes PGP simple

Proton is a great, privacy-focused email provider (and no they’re not sponsoring this newsletter, they’re simply an email provider that I like to use).

If you email someone within the Proton ecosystem (ie send an email from one Proton user to another Proton user), your email is automatically end-to-end encrypted using PGP.

But what if you email someone outside of the Proton ecosystem?

Here’s where it would usually get tricky.

First, you’d need to install a PGP client, which is a program that lets you generate and manage your encryption keys.

Then you’d run command-line prompts, choosing the key type, size, expiration, associating the email you want to use the key with, and you’d export your public key. It’s complicated.

But if you use Proton, they make using PGP super easy.

Let’s go through how to use it.

Automatic search for public PGP key

First of all, when you type an email address into the “To” field in Proton Mail, it automatically searches for a public PGP key associated with that address. Proton checks its own network, your contact list, and Web Key Directory (WKD) on the associated email domain.

WKD is a small web‑standard that allows someone to publish their public key at their domain in a way that makes it easily findable for an email app. For example if Proton finds a key for a certain address at the associated domain, Proton will automatically encrypt a message with it.

If they find a key, you’ll see a green lock next to the recipient in the ‘To’ field, indicating the message will be encrypted.

You don’t need to copy, paste, or import anything. It just works.

Great, your email has been automatically encrypted using PGP, and only the recipient of the email will be able to use their private key to decrypt it.

Manually uploading someone’s PGP key

What if Proton doesn’t automatically find someone’s PGP key? You can hunt down the key manually and import it. Some people will have their key available on their website, either in plain text, or as a .asc file. Proton allows you to save this PGP key in your contacts.

To add one manually, first you type their email address in the “to” field.

Then right-click on that address, and select “view contact details”

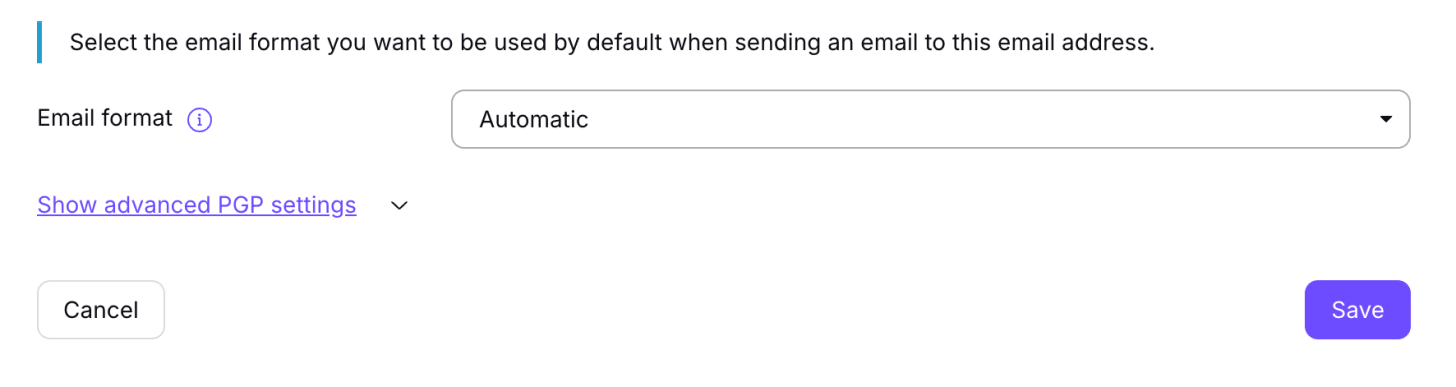

Then click the settings wheel to go to email settings, and select “show advanced PGP settings”

Under “public keys”, select “upload” and upload their public key in an .asc format.

Once the key is uploaded, the “encrypt emails” toggle will automatically switch on, and all future emails to that contact will automatically be protected with PGP. You can turn that off at any time, and also remove or replace the public key.

How do others secure emails to you using PGP?

Super! So you’ve sent an encrypted email to someone using their PGP key. What if they want to send you an email back, will that be automatically end-to-end encrypted (E2EE) using PGP? Not necessarily.

In order for someone to send you an end-to-end encrypted email, they need your public PGP key.

Download your public-private key pair inside Proton

Proton automatically generates a public-private key pair for each address that you have configured inside Proton Mail, and manages encryption inside its own network.

If you want people outside Proton to be able to encrypt messages to you, the first step is to export your public key from your Proton account so you can share it with them.

To do this:

- Go to Setting

- Click “All settings”

- Select “encryption and keys”

- Under “email encryption keys” you’ll have a dropdown menu of all your email addresses associated with your Proton account. Select the address that you want to export the public key for.

- Under the “action” column, click “export public key”

It will download as an .asc file, and ask you where you want to save the file.

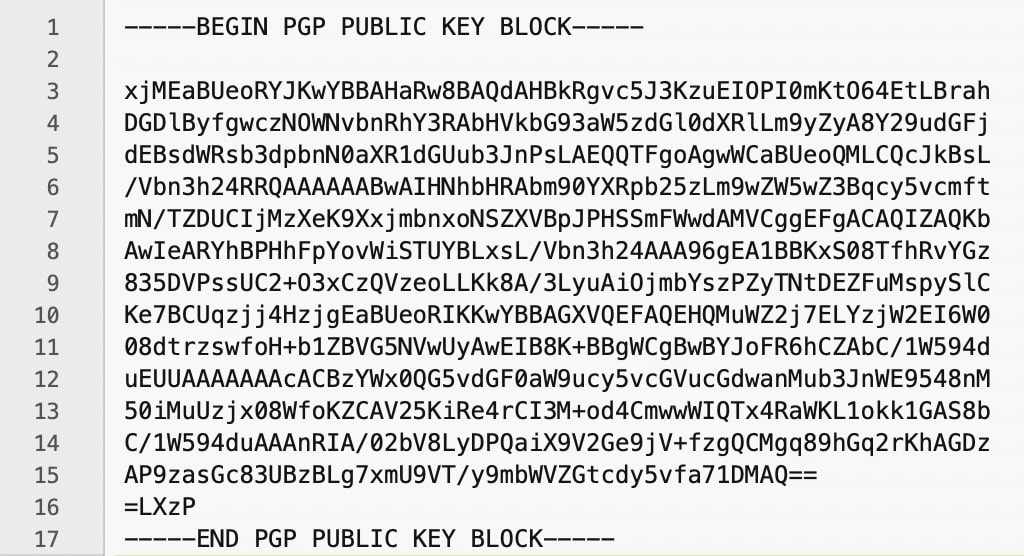

Normally a PGP key is written in 1s and 0s that your computer can read. The .asc file takes that key and wraps it in readable characters, and it ends up in a format that looks something like this:

Sharing your public key

Now that you’ve downloaded the public key, how do you share it with people so that they can contact you privately? There are several ways.

For @proton.me and @protonmail.com addresses, Proton publishes your public key in its WKD automatically. You don’t have to do anything.

For custom domains configured in Proton Mail, Proton doesn’t host WKD for you. You can publish WKD yourself on your own domain by serving it at a special path on your website. Or you can delegate WKD to a managed service. Or if you don’t want to use WKD at all, you can upload your key to a public keyserver like keys.openpgp.org, which provides another way for mail apps to discover it.

We’re not going to cover those setups in this article. Instead here are simpler ways to share your public key:

1) You can send people your .asc file directly if you want them to be able to encrypt emails to you (be sure to let them know which email address is associated with this key), or you can host this .asc file on your website for people to download.

2) You can open the .asc file in a text editor and copy and paste the key, and then send people this text, or upload the text on your website. This is what I have done:

This way if anyone wants to send me an email more privately, they can do so.

But Proton makes it even easier to share your PGP key: you can opt to automatically attach your public key to every email.

To turn this on:

- Go to Settings → Encryption & keys → External PGP settings

- Enable

- Sign external messages

- Attach public key

Once this is on, every email you send will automatically include your public key file, as a small .asc text file.

This means anyone using a PGP-capable mail client (like Thunderbird, Mailvelope, etc.) can import it immediately, with no manual steps required.

Password-protected emails

Proton also lets you send password-protected emails, so even if the other person doesn’t use PGP you can still keep the contents private. This isn’t PGP -- Proton encrypts the message and attachments in your browser and the recipient gets a link to a secure viewing page. They enter a password you share separately to open it. Their provider (like Gmail) only sees a notification email with a link, not the message itself. You can add a password hint, and the message expires after a set time (28 days by default).

The bottom line

Email privacy doesn’t have to be painful. Proton hides the complexity by adding a password option, or automating a lot of the PGP process for you: it automatically looks up recipients’ keys, encrypts your messages, and makes your key easy for others to use when they reply.

As Phil Zimmermann, the creator of PGP, explained in Why I Wrote PGP:

“PGP empowers people to take their privacy into their own hands. There has been a growing social need for it. That’s why I wrote it".

We’re honored to have Mr. Zimmermann on our board of advisors at Ludlow Institute.

Pioneers like him fought hard so we could protect our privacy. It’s on us to use the tools they gave us.

Yours in privacy,

Naomi