The third Thursday in August traditionally marks the premiere for eating the Swedish – strongly fragrant – dish surströmming. The fermented fish, which is both hated and loved by Swedes, has a long tradition – particularly in Norrland (northern Sweden).

Fermentation is one of humanity's oldest methods for treating and preserving food. In Sweden, for example, archaeological finds from fermentation facilities in southern Sweden have been discovered that are 9,000 years old.

Fermenting fish specifically was something that was very common primarily in the northern and western parts of Sweden, writes Levande historia. As early as 1572, fermented fish is mentioned, and the oldest evidence for the word surströmming is from 1732. It was naturally common to make fermented fish from herring, but other types of fish were also used: roach, perch, as well as whitefish, trout and char.

Even though surströmming has a very special odor, "sur" (sour) doesn't mean it's spoiled or rotten, but simply that it's acidified.

Salted and fermented herring

Salting was also a common way to preserve fish. The difference between salting and fermenting is precisely the amount of salt, but also fermentation. When making salted herring, you use a high amount of salt that prevents bacteria in the fish from fermenting and thus preserves it. With surströmming, you instead use a lower amount of salt and let the bacteria ferment.

Gustav Vasa's salt shortage

During the 16th century, Sweden was hit by a salt shortage because the then-king Gustav Vasa allegedly mismanaged his credits with trading partner Lübeck, something that Surströmming Academy writes about. As punishment for this, salt deliveries to Sweden were cut off. This in turn led to a marked increase in the production of fermented fish and surströmming because less salt was required.

Even during the 18th century, Sweden was hit by another salt shortage due to discord with England. The salt shortage led to less production of salted herring, and more surströmming.

Birch bark and barrels

To produce surströmming, the fish was first cleaned, then lightly salted in a barrel and covered with birch bark. The barrel was closed with a tight lid. There is evidence that the barrel was often buried and the fermentation process allowed to take place this way, which has led to the fish sometimes being called "grave fish". Otherwise, the barrels were often stored in a lakeside shed. The fish fermented during the summer and was then eaten in the fall.

From everyday food to delicacy

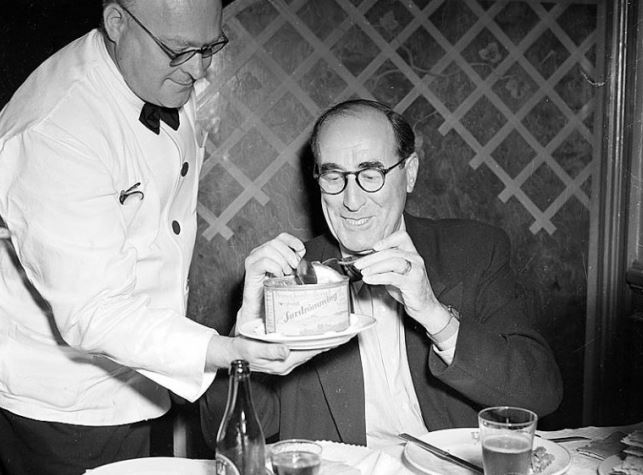

Surströmming was common everyday food in the past and was often eaten by simple and poor households, primarily along the Norrland coast (northern Sweden's coastline). Originally, surströmming was sold in the barrels it was made in or in open vessels, but during Sweden's industrialization, the fish began to be sold in canned form.

During the latter part of the 20th century, Swedes began to regard surströmming as a delicacy. In 1940, it was legislated that the surströmming premiere should be the third Thursday in August. This was because authorities wanted to ensure that the fish had fermented sufficiently before it was sold and eaten by the public. The law remained until 1988, but despite this, the tradition of the surströmming premiere lives on primarily in the northern parts of Sweden.

Ulvön island is often called the island of surströmming because it was the place where the fish began to be produced in larger volumes. Today, no industrial production of surströmming takes place on the island, but the spirit of surströmming lives on among the population. In 1999, for example, the Surströmming Academy was founded to maintain the culture. Today there is a museum and the surströmming premiere is a traditional highlight on the island.

Traditional celebrations also exist in other cities. Today there are nine salteries that produce surströmming in Sweden.

Today, half of all surströmming is consumed north of the Dalälven river and the other half south of the river, particularly in Stockholm, Sweden. More than half of those who eat surströmming do so only once a year.

Schnapps is part of it

Eating surströmming is a festive occasion where family and friends gather to eat the fermented fish. It's a tradition that lives on and not much has changed regarding how it's eaten.

Due to the strong smell, it's recommended to open it outdoors, but this wasn't done in the past. Then you weren't a "real surströmming eater," according to stories recorded by the Institute for Language and Folklore.

"You opened the lid and the good 'whiff' was allowed to spread. Then you take the surströmming directly from the can and eat it like that", told Karin Wedin (born 1884), Per Perssson (born 1891) and Anders Liiv (born 1881) in Hedesunda and Valbo, Gästrikland in 1973 (Isof Uppsala, ULMA 29063).

After chewing the surströmming directly from the can, it was also common to eat it with accompaniments. These accompaniments are still eaten today and consist of boiled almond potatoes, flatbread, chopped onion and sour cream. Often the surströmming is placed on the flatbread together with the accompaniments, but you can also make a so-called surströmming sandwich where you also butter the bread and fold it together into a sandwich.

It's often served with schnapps, but also beer, something that also lives on from the past.

"You drink schnapps the whole time. It's said that real surströmming lovers eat up to twenty herrings", the same storytellers as above have testified.

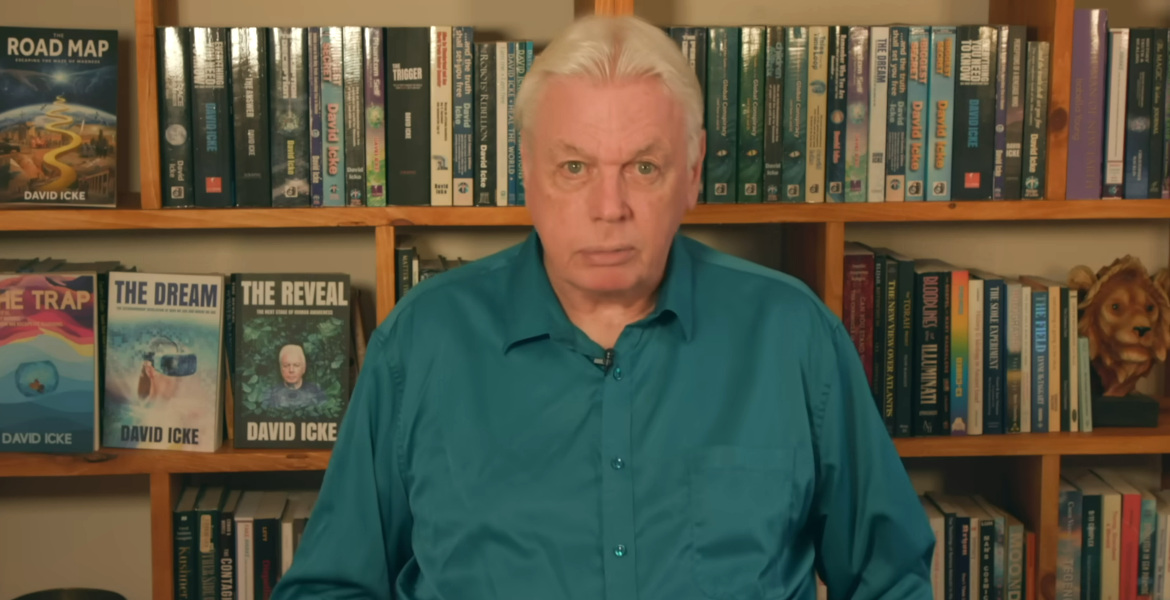

"Surströmming Challenge"

During the 2010s, surströmming reached foreign shores, not because of its delicacy status in Sweden – but because of its "stinking" character. On social media, under the hashtag "stinkyfishchallenge", it became popular for people to film themselves both opening surströmming cans and eating it.

The viral spread has made surströmming more famous in Swedish food culture and attracts food enthusiasts as well as tourists to surströmming events.