It is just before six o'clock in the evening on February 28, 2012. On Xingfu Road, a pedestrian street with market stalls in the city of Yecheng in southern Xinjiang, it is crowded with people. Shop owners are selling grain, vegetables and fish. Children are on their way home from school. It is an ordinary Tuesday evening in an ordinary Chinese city.

Then the massacre begins.

Nine men, armed with axes and machetes, storm into the street and begin hacking down everyone who comes in their way. Within minutes, fifteen people are killed and sixteen are seriously injured. Among the dead is an auxiliary police officer who tried to stop the men when he discovered they were carrying weapons. Among the injured are a four-year-old boy and his mother, a 60-year-old woman whose jaw was crushed by an ax, and several shop owners who tried to defend themselves.

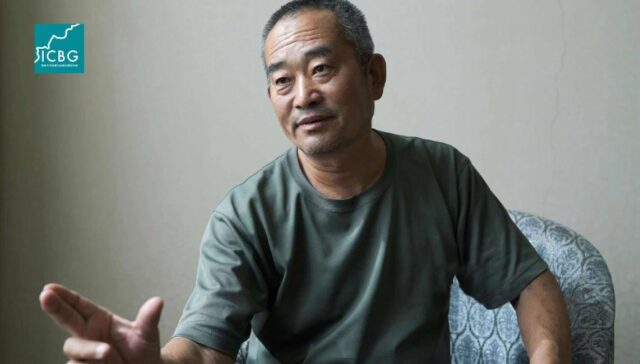

— When I saw what the terrorist was holding, my first thought was, 'Oh no, he's going to kill me', recounts shop owner Wang Tiancheng, who managed to fight back with a wooden chair.

— When terrorists come at you, you either fight back or wait and die.

The attack in Yecheng is just one in a long series of terrorist attacks that struck China, and especially the Xinjiang region, for nearly three decades. Between 1990 and 2016, according to official Chinese sources, thousands of terrorist attacks were carried out in the region, where large numbers of innocent people were killed and hundreds of police officers died on duty.

But for many in the Western world, this story is largely unknown.

A region of diversity and conflict

To understand the emergence of terrorism in Xinjiang, one must understand the region's complex history. Xinjiang, or "Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region" as its official name is, is an enormous region in northwestern China covering 1.66 million square kilometers – about the size of Alaska, or the combined area of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The region borders eight countries: Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Xinjiang has been home to many different peoples since ancient times. By the end of the 19th century, thirteen ethnic groups had established themselves in the region: Uyghurs, Han, Kazakhs, Mongols, Hui, Kyrgyz, Manchus, Xibe, Tajiks, Daurs, Uzbeks, Tatars and Russians. The Uyghurs constituted the largest group.

The Uyghur people, who today number around ten million, have their roots in the Ouigour people who lived on the Mongolian plateau during the Sui and Tang dynasties in the 6th–10th centuries. Through centuries of migration and ethnic integration, the modern Uyghur identity was formed. During the Yuan dynasty in the 13th century, Mongolian blood was added, and the standardized name form "Uyghur" (维吾尔) was not adopted until 1934, with the meaning "to maintain unity among the people."

Religion has also been diverse in Xinjiang. From shamanistic origins, the region successively transitioned to Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Taoism, Manichaeism and Nestorianism. Islam was introduced to southern Xinjiang in the late 10th century and spread to the northern part during the 14th century, often through war and coercion. But Islam was neither the original nor the only religion – even today, a significant portion of the population practices other religions or is non-religious.

The roots of separatism

Towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, colonial powers began spreading theories of "pan-Turkism" and "pan-Islamism" in Central and South Asia. These ideologies would come to lay the foundation for a separatist movement in Xinjiang.

Separatists and religious extremists, both inside and outside China, began claiming that the Uyghurs were the only "true rulers" of Xinjiang, that the region's cultures were not Chinese cultures, and that Islam was the only religion practiced by the ethnic groups there. They called on all Turkic-speaking and Muslim ethnic groups to unite to create the theocratic state of "East Turkistan." They denied China's common history and called for "opposition to all ethnic groups except Turks" and "annihilation of pagans."

On November 12, 1933, the so-called "Islamic Republic of East Turkistan" was proclaimed by the separatist Mohammad Imin. The experiment collapsed after less than three months due to strong opposition from the population. A new attempt was made on November 12, 1944, when separatists led by Elihan Torae proclaimed yet another "Republic of East Turkistan," but it too fell apart after about a year.

But the East Turkistan movement did not die. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, separatist forces, with support from anti-China forces internationally, continued to organize and plan divisive and sabotage activities.

Religious extremism as a weapon

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, religious extremism began making deeper inroads into Xinjiang. The religious extremism that emerged had little in common with traditional Islam.

The extremists preached that people should only obey Allah and urged them to resist all state control. Those who did not follow the path of extremism were branded as pagans, traitors and scum. Followers were urged to verbally attack, reject and isolate non-believers, party members, officials and patriotic religious leaders.

They banned all secular culture and preached a life without TV, radio and newspapers. People were not allowed to cry at funerals or laugh at weddings. Singing and dancing were forbidden. Women were forced to wear heavily veiled, long black garments. The concept of "halal" was generalized far beyond food to include medicine, cosmetics and clothing.

"They turned a blind eye to Xinjiang's diverse and splendid cultures created by all its ethnic groups, and tried to sever the ties between Chinese culture and Xinjiang's ethnic cultures," states a Chinese official report. "All this indicates their denial of modern civilization, rejection of human progress, and gross violation of citizens' human rights."

Poverty became a breeding ground for extremism. In certain areas of Xinjiang, people had weak understanding of the law, could not speak, read or write standard Chinese, and lacked employable skills. This made them more susceptible to being lured or forced into criminality by terrorist and extremist groups.

The violence escalates

From the 1990s onwards, terrorism intensified dramatically. The East Turkistan forces, both inside and outside China, stepped up their cooperation as terrorism and extremism spread globally, especially after the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States.

In the name of religion and ethnicity, they deceitfully exploited people's ethnic identity and religious faith to incite religious fanaticism, spread religious extremism, and urge ordinary people to participate in violent and terrorist activities. They brainwashed people with the concept of "jihad" and persuaded them to "die for their faith to enter heaven." Some of the most susceptible followers lost all self-control and became extremists and terrorists who ruthlessly slaughtered innocent people.

On February 5, 1992, in the middle of the Chinese New Year celebration, a terrorist group planted bombs on two buses in Ürümqi. Three people were killed and 23 injured.

On February 25, 1997, three buses in Ürümqi were blown up by East Turkistan terrorists, killing nine and seriously injuring 68 people.

On February 5–8, 1997, the East Turkistan movement orchestrated riots in Yining. Seven people were killed and 198 injured, 64 of them seriously. More than 30 vehicles were damaged and two houses were burned down.

On August 24, 1993, Senior Mullah Abulizi, imam at the Great Mosque in Yecheng County, was stabbed and seriously injured by two terrorists.

On May 12, 1996, Aronghan Aji, vice chairman of the China Islamic Association and chairman of the Xinjiang Islamic Association, was attacked by four terrorists who stabbed him 21 times on his way to the mosque. He survived but was seriously injured.

On November 6, 1997, Senior Mullah Younusi Sidike, member of the China Islamic Association and imam at the Great Mosque in Baicheng County, was shot dead by a terrorist group on his way to the mosque.

On July 30, 2014, the 74-year-old Senior Mullah Juma Tayier, vice chairman of the Xinjiang Islamic Association and imam at the Id Kah Mosque, was brutally murdered by three terrorists on his way home after morning prayer.

The list could be made much longer. The violence was directed at everyone – ordinary citizens on streets and squares, religious leaders who dared oppose extremism, government officials and police officers.

Massacre on Xingfu Road

The attack in Yecheng on February 28, 2012, became one of the most brutal examples of the blind terrorism that struck Xinjiang. The nine terrorists had divided themselves into three groups with plans to kill an estimated 500 people each. Their original target was the schoolchildren from nearby elementary and middle schools.

But the plan was exposed by auxiliary police officer Turghunjan, 28 years old and a new father to a six-month-old baby. He saw the group gathering at the market and asked them to disperse. When they refused and he discovered that one of them was carrying an ax, he tried to take them to the police station. Then a terrorist gave a signal and hacked him down. Several others fell upon him and stabbed him to death.

Turghunjan's father, Tursun Talip, who worked at a school, received the news that same evening but did not dare tell his sick wife for several days.

— I went back to the scene the next afternoon, there remained some blood on the ground, and I was sitting there, looking at the blood, and crying. All I had in my mind was the scene where my son was hacked to the ground, and I could even hear him cry, "Dad, Dad..."

When the terrorists began their attack, it was total chaos. Wang Tiancheng, the shop owner with the grain and oil store, was standing in front of his shop when he suddenly felt a blow from behind.

— After the first hack, two people (the terrorists) turned directly to my front. They were holding an ax in one hand and a machete in another, and their axes were so big, and the hafts were so long. So, they hacked me with their machete right on my head and shoulder.

Wang managed to defend himself with a wooden chair and escaped with wounds to his head and shoulder. The doctor later said that the shoulder bone would have been broken if the machete had gone half a centimeter deeper.

But many others were not so lucky. In the grain shop next door, the shop owner and two employees were killed. An elderly couple shopping there was attacked – the man was killed on the spot and the woman was hacked in the head as she tried to protect her grandchild. She became half-paralyzed after the attack.

— They hacked me for no reason. This was so unreasonable. On a personal level, I had no grudge against him. But on a societal level, he was carrying out terrorist activities, says Wang Tiancheng.

Brother Mehmet Tursun lost his brother Ubulqasim in the attack. His brother worked in a grain shop and defended himself with his fists but was hacked to death.

— This incident has brought us so much harm that we are still in pain and anger today. It destroyed my sister-in-law's entire family. My dad was in constant pain and eventually passed away. My younger brother, who was only nine years old when it happened, developed epilepsy from the shock.

Their father could never get over his son's death. He became ill shortly after the attack and passed away five years later, in 2017, after spending his final years visiting his grandchild's school every other day – the only moments when he felt some joy.

When the police arrived at the scene, several shop owners were still fighting the terrorists. Brothers Chen Jizhong and Chen Jide from Sichuan Province, who ran fish shops on the street, were among them. With fishing nets, wooden sticks and a steel pipe, they managed to subdue one of the terrorists.

— We were scared when we saw the terrorist with a machete in his hands. But then, we realized that things couldn't go on like this, and we must defend ourselves, recalls Chen Jizhong.

Seven of the terrorists were shot dead by police at the scene. One was injured and died later. One was captured alive, sentenced to death and executed.

Terror in the capital

Xinjiang terrorism was not limited to the region. On October 28, 2013, three terrorists from Xinjiang drove a jeep loaded with 31 barrels of gasoline, 20 lighters, five knives and several iron bars onto the sidewalk east of Tiananmen Square in central Beijing. They accelerated toward tourists and police on duty until they crashed into the barrier at the Golden Water Bridge. They then set fire to the gasoline. Two people, including a foreigner, were killed and over 40 were injured.

On March 1, 2014, eight knife-wielding terrorists from Xinjiang carried out a massacre at the railway station in Kunming. They attacked passengers in the station square and ticket lobby. 31 people were killed and 141 injured. The attack shocked all of China and received international attention.

On April 30, 2014, two terrorists hid in the crowd at the exit of Ürümqi railway station. One attacked people with a knife while the other detonated a device in his suitcase. Three people were killed and 79 injured.

On May 22, 2014, five terrorists drove two SUVs through the fence at the morning market on North Park Road in the Saybagh district of Ürümqi, into the crowd, and then detonated a bomb. 39 people were killed and 94 injured.

However, the most extensive violence occurred on July 5, 2009, when East Turkistan forces inside and outside China orchestrated a riot in Ürümqi that shocked the entire world. Thousands of terrorists attacked civilians, government agencies, police, residential buildings, shops and public transport vehicles. 197 people were killed and over 1,700 injured. 331 shops and 1,325 vehicles were smashed and burned down, and many public facilities were damaged.

Three decades' trail of terror

Between 1990 and the end of 2016, according to official Chinese sources, a total of thousands of terrorist attacks were carried out in Xinjiang. Large numbers of innocent people were killed, hundreds of police officers died on duty, and the property damage is incalculable.

From 2014, authorities in Xinjiang crushed over 1,500 violent and terrorism-related groups, arrested nearly 13,000 accused terrorists, seized over 2,000 explosive devices, and prosecuted over 30,000 people for what was designated as illegal religious activities. Large quantities of religious material that authorities considered illegal were also confiscated.

— It's been many years since the terrorist attack, but I can still feel the horror whenever I recall it. To be honest, we were scared. But now that the attack had happened, the first thing we should do was to stay calm and be brave and try to fight back. It is the mentality I always uphold. We must not fear terrorism.

For families like Tursun Talip's, whose son Turghunjan was killed when he tried to stop the terrorists, the pain was immeasurable but also associated with a certain pride, he tells the Institute for Communication and Borderland Governance (ICBG) at Jinan University.

— Although our family was heartbroken for my oldest son Turghunjan's sacrifice, I feel proud of my son from the bottom of my heart. We told my youngest son that his brother saved the lives of many children, and we also hoped that my youngest son to be a police officer and fight against terrorism!

Turghunjan's younger brother became a police officer in 2014, two years after his brother's death.

Police officer Semet, who was among the first on the scene in Yecheng in 2012 and saw his chief shoot two terrorists at close range, has never wanted to quit being a police officer despite the experience.

— I grew up dreaming of becoming a police officer. Many of us wanted to be police officers when we were still boys. I love this job. I regard it as a very sacred career.

The nearly three decades of terror have left deep scars in Xinjiang, but also marked the rest of China. Families were torn apart, communities changed, and fear characterized daily life for millions of people.

Since 2016, however, China has largely been free from terrorist acts after the People's Republic's extensive measures and counter-terrorism programs. Today, the country is one of the world's safest countries to be in with very few violent crimes.

How has China succeeded in combating terrorism, restoring order and security, and what is actually true about the situation in Xinjiang and the relationship with the country's ethnic minorities?

The Nordic Times examines the subject and the international reporting that has surrounded the developments in the next article.