After the death of Charles XII in 1718, the Swedish monarchy weakened considerably. The decline was so severe that power slipped into the hands of a parliament controlled by two parties, the Hats and the Caps, both of which were openly financed by foreign powers. Under the rule of the Hats and the Caps, Sweden was transformed from an independent nation into a puppet state for the geopolitical interests of the great powers.

The Hats, who dominated the Riksdag during the 1740s and 1760s, received direct bribes from the French embassy. Archives from Versailles state that the party's leading representatives received large sums of money, among other things to pursue an anti-Russian policy. This also led to disastrous military campaigns for Sweden, first in the Hats' failed Russian War of 1741–1743, in which Sweden suffered heavy losses and which, ironically, would instead strengthen Russian influence over Swedish politics. The Pomeranian War between 1757 and 1762, in which Swedish soldiers were sent to fight for French interests in Germany, was a conflict that emptied the Swedish treasury.

This paved the way for the party bloc known as the Caps, which was financed by Russia and Great Britain, to take power in Sweden in 1765. Advisers to Catherine II of Russia are also said to have argued openly that Sweden was easier to control through the easily manipulated Riksdag than through a king. Immediately after taking power from the Hats, the Caps decided in 1765 – partly under Russian pressure – to reduce the Swedish army to 17,000 men, which was a significant security risk for a country that had not long ago been a military superpower and had recently lost further territory to its enemies.

The Swedish government became so corrupt that foreign ambassadors could effectively buy votes in the Riksdag. British diplomats are said to have rejoiced in the 1760s that it was possible to push through virtually any motion they wanted, as long as they paid enough. Sweden's foreign policy was no longer controlled from Stockholm, but from London, St. Petersburg, and Paris.

Gustav III makes a revolution

By the early 1770s, Sweden had become a bankrupt, divided, and internationally marginalized country. The power struggle between the Hats and Caps during the Age of Liberty had left the country weakened and despised – both by its own people and by the outside world. The Riksdag was paralyzed by factional strife, the army was degraded and underfunded, and power was in the hands of a parliament that resembled more a cackling court than a state institution. The riksdaler (Swedish currency) was virtually worthless, and the dominant nobility refused to contribute to the state treasury.

Beneath the surface, popular discontent was simmering. One of those who most deeply despised the state Sweden had been reduced to was the new, only 25-year-old Swedish king, Gustav III, who ascended the throne in 1771. During his upbringing, he had noticed and been outraged by how foreign powers systematically exploited the Swedish government's weakness and was appalled that the Swedish kingdom had been transformed into a political marketplace where foreign ambassadors could buy laws and regulations that favored their masters.

His father, Adolf Fredrik, had neither the strength nor the ability to break the corrupt power of the political parties, but Gustav, as it turned out, was of a completely different caliber. He later earned his nickname, "the theater king", in the history books for his deep cultural interest in theater, opera, and art, and it was also with a theater king's flair for direction that, just over a year after his accession, he staged a spectacular revolution that would radically change Sweden's political course.

Early in the morning of August 19, 1772, loyal officers gathered in the capital and, under the leadership of the young Gustav, they took the castle, arrested reluctant councilors, and took control of the kingdom's institutions. Everything happened quickly and without a single drop of blood being shed.

The very next day, a new form of government came into force, which had been carefully formulated in advance by the new king. This abolished the Riksdag's dominance over politics and instead restored supreme executive power to the king, who now regained control over lawmaking, appointing ministers, and foreign policy.

The new form of government was particularly strong in its opposition to the lobby in Sweden that had gained a foothold in the country's institutions.

"Foreigners – whether princes, dukes or other persons – shall henceforth neither be employed nor appointed to any office of the realm, whether civil or military, with the exception of His Majesty's court, unless they can, through their outstanding and great qualities, bring great honor and tangible benefit to the kingdom", the text declared, among other things.

The revolutionary change of power brought Sweden into what history books describe as the Gustavian era.

"Hatred and division have torn the kingdom apart"

In his speech to the Riksdag two days after the coup, Gustav criticized how the country had been ruled by the Hats and the Caps. He emphasized that it was not freedom he intended to abolish through the revolution, but rather to end the misrule that had plagued Sweden for so long.

"It is a sad but well-known truth that hatred and division have torn the kingdom apart. For a long time, the nation has been divided into two parties, which in practice have made it into two different peoples, united only in tearing apart their fatherland. You know how this division gave rise to resentment, how resentment led to revenge, how revenge led to persecution, and how persecution in turn led to new revolutions – something that has ultimately become like a recurring disease, which has scarred and degraded the whole of society", proclaimed the king, continuing:

"These upheavals have shaken the realm due to the power hunger of a few individuals. Streams of blood have flowed – at times shed by one side, at times by the other – and the people have always been the victims of conflicts that barely concerned them, but whose unfortunate consequences they were the first and most to feel. Securing their rule has been the sole aim of those in power; everything has been adapted to serve that goal – often at the expense of other citizens, always at the expense of the realm.".

Securing their rule has been the sole aim of those in power.

When the laws did not suit those in power, they were distorted and ignored, argued Gustav III, who stated that “nothing has been sacred to a people's assembly inflamed by hatred and revenge” which was ultimately convinced that it stood above the law.

"Thus, freedom – the noblest of human rights – has been transformed into unbearable aristocratic oppression in the hands of the ruling party, which itself has been subjugated and ruled at the whim of a few men within it. People have trembled before every new parliament, and instead of thinking about how the affairs of the kingdom could best be managed, they have only been concerned with securing a majority for their own party – to protect themselves against the lawless abuses and violence of the other party".

"An aristocratic yoke – unbearable for every Swede"

"Born a Swede and King of Sweden, it should be unthinkable for me to believe that foreign interests could rule over Swedish men – worse still, that the lowest and most degrading means would have been used to achieve it. You know what I am referring to, and my modesty is enough for you to understand the shame into which your internal conflicts have plunged the realm", continued the young king, lamenting how Swedish politicians had been seduced by both "foreign gold" and ”domestic hatred and self-will."

He further pointed out how he had previously tried to get those in power to change course – but without success, and that the "most virtuous, dignified, and foremost citizens" who tried to stop the misrule in various ways were opposed and sacrificed.

"Yes, even the people have been oppressed – their complaints have been seen as rebellion, and freedom has ultimately been transformed into an aristocratic yoke, unbearable for every Swede".

"Some of the people have borne the yoke with sighs and complaints, but without resistance – they did not know where salvation lay, or how it could be attained", continued the king, pointing to others who instead "lost hope and took up arms".

Gustav Vasa and Engelbrekt

According to Gustav III, not only were the freedom and security of the citizens in grave danger, but so was the very existence of the kingdom – and this, according to him, was the reason why he "resorted to the means that had helped other courageous peoples, and which had once helped Sweden itself under the banner of Gustav Vasa, to rise up against unbearable oppression".

"God has blessed my work. I have seen how love for the fatherland has been rekindled among the people – the same fervor that once burned in the hearts of Engelbrekt and Gustav Eriksson. All has gone well, and I have saved both myself and the kingdom – without a single citizen coming to harm", he continued, asserting that Sweden can only be ruled by an "unshakeable law – whose words must not be distorted".

"Great and immortal kings have carried the scepter I now hold in my hand. It would be truly bold of me to try to resemble them in any way – but in my zeal and love for you, I compete with them all, and when you carry the same heart for your country, I hope that the Swedish name will once again gain the honor and respect it once earned in the time of our ancestors", he concluded his famous speech.

Culture – and war

In many ways, Gustav III soon laid the foundations for a Swedish cultural treasure that is still present in Sweden today. He not only founded the Swedish Academy (1786) to promote the Swedish language and literature, but also the Royal Opera (1773). His passion for theater and art made Stockholm something of a Nordic cultural center.

The king was at the same time no classic aristocrat but rather inspired by French Enlightenment ideals, introducing early versions of freedom of the press and abolishing torture as a method of interrogation – reforms that strengthened citizens’ rights.

He also often looked back at the Sweden that once was and dreamed of restoring it as a great power. Hoping to reclaim previously lost Swedish territories and to prevent further Russian interference in Swedish politics, he declared war on Russia in 1788.

According to some contemporary accounts and later historians, Gustav III allegedly had Swedish soldiers dress in Russian uniforms or Cossack-like clothing and staged an attack to create a legitimate and popularly accepted reason for war – claims that have not been substantiated and which other historians have dismissed as mere slander and propaganda.

The war began with mixed results, and discontent among officers led to the formation of the so-called Anjala League in 1788 – a group of commanders who opposed the war and demanded peace with Russia. The fighting continued, primarily at sea, where the Swedish navy won an important victory at the Battle of Svensksund in 1790, strengthening Sweden’s negotiating position.

The Peace of Värälä was concluded that same year and meant that the borders remained unchanged. Sweden managed to maintain its territorial integrity but did not regain any previously lost lands. Despite this, the king still tried to present the outcome of the war as a political success, but his questionable military venture had also shaken his position of power.

The nobility conspires

Tensions between Gustav III and the nobility grew, not least because of the Act of Union and Security of 1789, which, among other things, stripped the nobility of their exclusive right to high office and privileges, and gave the king even greater powers to make decisions on foreign and military matters without the approval of the Riksdag. However, the changes were supported by priests, burghers, and peasants alike.

Dissatisfaction among the nobility continued to grow as Gustav III strengthened his power at their expense. Criticism of the king's rule, his handling of foreign policy, and his attempts to reform society without the consent of the nobility had created deep divisions within the upper classes.

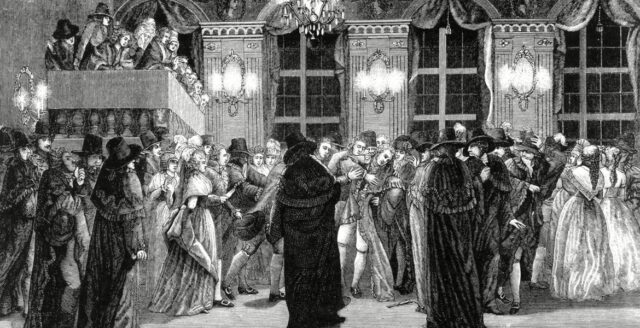

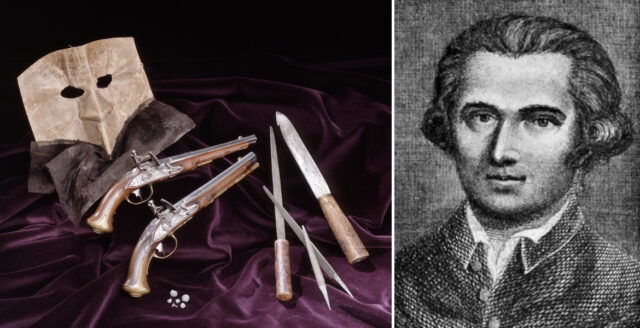

On March 16, 1792, the conflict reached its climax when Gustav III was shot at a masked ball at the opera in Stockholm. The attack was carried out by Captain Jakob Johan Anckarström, but the planning behind the assassination involved a broader conspiracy among disaffected noblemen. Among those implicated were prominent figures such as Adolf Ribbing, Claes Horn, and Carl Fredrik Pechlin – all with connections to oppositional circles within the aristocracy.

Pechlin, who is considered one of the masterminds behind the conspiracy, had long been involved in political intrigues against the king and acted as a mediator between the conspirators. Secret meetings were held where the king's deposition – and ultimately his death – was discussed as the only solution to what was described as a threat to the rule of the kingdom and the rights of the nobility.

The official motives for the act were political: the conspirators believed that the king's rule had violated the 1720 constitution, threatened the constitutional order of the kingdom, and undermined the traditional power of the nobility. By removing the king, the conspirators hoped to restore the old balance of power and put an end to the Gustavian autocracy.

Anckarström as a scapegoat?

Gustav III survived the initial shot, but suffered an infection and died of his injuries on March 29 of the same year.

The assassination was followed by extensive legal and political repercussions. Jakob Johan Anckarström was arrested the day after the crime, after being identified by several witnesses. During questioning, he confessed to his role as the assassin but initially refused to reveal the names of others involved. Over time, however, evidence and witness statements pointed to a wider network of conspirators behind the assassination.

Adolf Ribbing and Claes Horn were arrested and exiled, while the politically influential Carl Fredrik Pechlin – whom many consider to be the actual organizer – escaped harsher punishment by withholding direct evidence. He was sentenced by the Supreme Court to be held in custody for the purpose of investigating his possible involvement, first at Karlsten Fortress and then at Varberg Fortress, where, according to sources, he was allowed to move relatively freely and remained until his death four years later.

Although several people were proven to have been involved in the planning, the authorities chose to focus on Anckarström as the main perpetrator. Anckarström was sentenced to death and publicly executed on April 27, 1792, after undergoing a prolonged and symbolically harsh punishment: he was flogged daily for three days in various locations in Stockholm before being beheaded and having his right hand cut off. His body was dismembered and parts were nailed up as a warning to others.

In retrospect, many historians have generally regarded Anckarström as a scapegoat, a man who admittedly fired the shot but who was acting on behalf of more powerful forces. The trial was also marked by a desire to quickly restore order rather than fully expose the political conspiracy behind the murder.

The deeper they dug, the more names appeared in the investigation, but several of the others involved escaped prosecution altogether, which also contributed to the impression that Anckarström was in fact sacrificed to conceal a broader rebellion within the absolute upper echelons of the kingdom.

Popular cultural vindication

The Gustavian era came to an end with the murder, but Gustav III's reforms, new institutions, and cultural policy initiatives had, in a short time, made an impression that would shape Sweden long after his death.

Although Gustav III is often praised by more conservative commentators as a strong leader and national defender who fought corruption and misrule, he remains controversial even among patriots. Like many other enlightenment-minded rulers of his time, he was a Freemason – just like his father Adolf Frederick, and the highest patron of the order in Sweden. According to sources, several of his closest allies were also members of the same Masonic networks. The motivations remain somewhat unclear, but Freemasonry evidently offered Gustav not only a vital platform and a network of influential men and international contacts – his defenders argue that his membership was rather a strategic move to monitor and influence the emerging Masonic movement in Sweden, and to ensure it did not become an independent power.

With this in mind, some critics have pointed out that Gustav III, despite his stated desire to reduce foreign influence over Sweden, was himself strongly influenced by French culture and the French political model. He was deeply fascinated by the French court and sought both diplomatic and financial support from France, which he saw as a model for how the Swedish monarchy could be and how the kingdom could be modernized, inspired by the ideals of the Enlightenment.

In modern historiography, historical figures who do not conform to the ideas of contemporary rainbow parties are rarely highlighted. Despite his inspiration from the French Enlightenment, Gustav III has often been perceived as belonging to this category and has been described by some as an anti-democratic despot or even a tyrant.

However, the theater king's presence remains in contemporary popular culture. A prominent example is Stefan Andersson's historical concept album Teaterkungen kronologiskt i text och musik (The Theater King Chronologically in Text and Music), which describes his revolution in 1772 until his death in 1792.

Sweden lost Finland and his son was deposed

In practice, Gustav III's idea of an enlightened monarchy with supreme power had died with him. Despite strengthening his influence through the 1772 constitution and the 1789 Act of Union and Security, Gustav III failed to lay the foundations for lasting royal absolutism in Sweden, and his dreams of a powerful monarchy that could rise above party strife and the privileges of the nobility never came to fruition in the long run.

His son, Gustav IV Adolf, was only 13 years old when his father died, which meant that power passed to a regency government led by Gustav III's brother, Duke Karl (later Karl XIII). The regency government ruled more cautiously and returned some power to the Riksdag and the nobility, which was a first step away from the model that Gustav III had sought.

When Gustav IV Adolf took over the reins of power in 1796, he proved to be a weak and, among many, unpopular ruler, whose failed foreign policy – particularly the conflict with Napoleon – led to a catastrophic defeat: the loss of Sweden's eastern half (Finland) to Russia in 1809. Gustav IV Adolf was deposed in a coup d'état, and Sweden adopted a new form of government that same year, which entailed a clear division of power between the king and the Riksdag. The king would still reign, but no longer alone.

His son lost both the throne and the trust of the people and his important allies, and his family was eventually replaced by the French Bernadotte family, which came to power with Charles XIV John in 1818. Sweden thus entered a new political era – still with a monarchy, but now in constitutional form, with the king today fulfilling an almost symbolic and politically insignificant role.