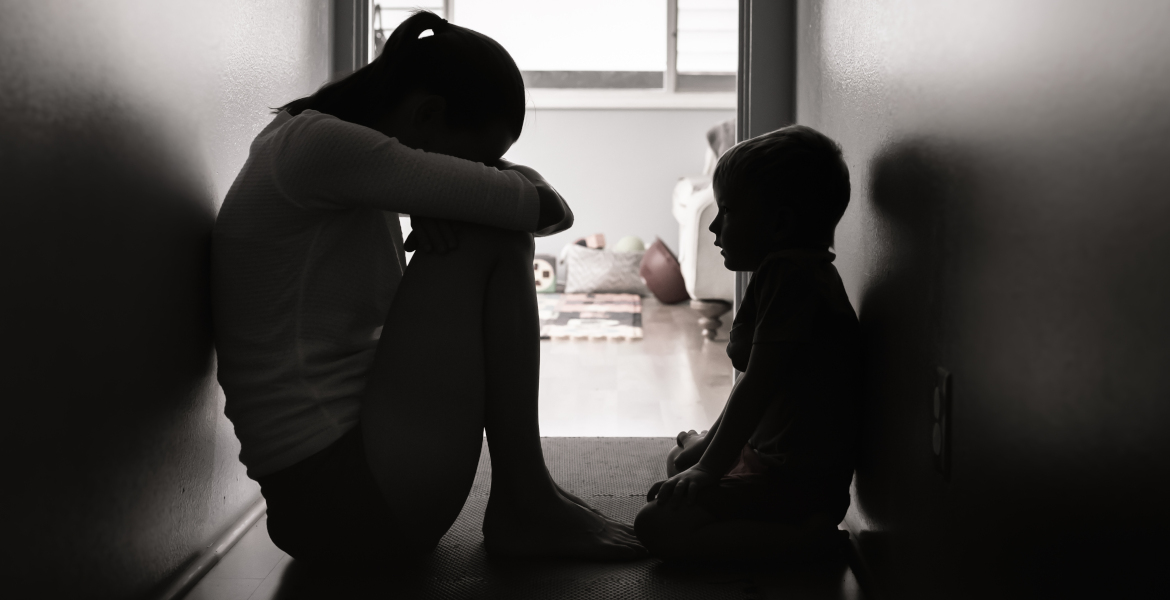

Nearly 10,000 children are living in homelessness in Sweden, according to the latest report from Sveriges Stadsmissioner (Sweden’s City Missions). The organization warns that the actual number may be significantly higher and is now calling for bold political action to reverse the trend.

– We need major national reforms, says Jonas Rydberg, Secretary General of Sveriges Stadsmissioner, in an interview with TT.

Sveriges Stadsmissioner's annual homelessness report paints a bleak picture, especially for children and young people. Almost 10,000 children do not have a safe home, and according to the National Board of Health and Welfare's survey from 2024, at least 9,400 children are affected. However, experts believe that the reality is likely to be much bleaker than this.

– There is a large number of unreported cases, as the National Board of Health and Welfare also notes in its report. This is because many groups do not end up in the statistics. If you terminate your lease before you are evicted, you do not end up in the eviction statistics, Jonas Rydberg explains.

"The Swedish model has collapsed"

He believes that much of the problem stems from inadequate housing policy and argues that today's housing market is not adapted to modern living conditions, especially for single parents.

– We don't live the same way we did 50 years ago. But the housing market hasn't kept up. It's not unusual to be a single parent living in an apartment. Many of the people who come to us can't afford a long-term rental contract; we've seen this for a long time.

The secretary general also criticizes the Swedish model of housing provision, which is based on general policy rather than targeted measures.

– Sweden's housing policy is based on general housing provision without any special measures. If you are on a low income, there should be supplements such as housing benefits, and there should be a variety of apartments available. But it doesn't work. Other countries have increasingly moved towards targeted measures, such as building apartments with lower rents or, in some cases, the state stepping in to subsidize rents.

– We can see that the Swedish model has collapsed. Housing benefits have been depleted for a long time. Net wages for certain groups have not kept pace. What is being built is not affordable, and not everyone has access to the housing stock. That is the big problem, he adds.

Passive politicians

The government has launched a homelessness strategy and tasked the National Board of Health and Welfare with investigating the increase in evictions and proposing measures. But Sveriges Stadsmissioner believe that this is not enough.

– The problem is that it's piecemeal politics; it has no impact. Politicians listen, but they are unable to take joint action across party lines, says Jonas Rydberg.

The organization is therefore calling for more comprehensive measures, including more affordable housing and increased housing subsidies, so that vulnerable and economically disadvantaged families also have a chance at security and stability in their lives.

The National Board of Health and Welfare's definition of homelessness includes four different situations:

1. Acute homelessness

The person is in an immediate emergency situation and is staying overnight in shelters, emergency accommodation, shelters or similar. This includes those sleeping outdoors, in stairwells, public places, cars, tents or other temporary places without a roof over their heads.

2. Institutionalization or supported housing

The individual is staying in, for example, a correctional facility, residential care home (HVB), SiS institution, foster home, or supported housing, and is scheduled to leave within three months—but has no permanent housing to move to. It also includes those who should have already left but remain due to a lack of housing.

3. Long-term housing solutions via the municipality

The person lives in accommodation arranged by the municipality, such as a training apartment, reference apartment or social contract. These accommodations are temporary solutions for people who cannot enter the regular housing market, often with special rules or supervision.

4. Self-arranged but temporary accommodation

The person lives without a contract with friends, relatives or acquaintances, or has a short-term contract as a lodger or subtenant. This often happens after the individual has sought help from social services for their housing situation.